Teaching Yoga for Anxiety

Feb 05, 2021

Whilst teaching yoga for a specific condition might be termed as therapeutic yoga, when it comes to anxiety, even when teaching a group class, we can be pretty assured to have someone included who has experience of anxiety. Whether this is more reactive heightened stress states to a particular event or current circumstances, or deeper ‘trait’ anxiety where anxious states dominate day-to-day living. Many people who tend to ‘social anxiety’ may even feel that arising within the context of a yoga class, where there is close proximity to others, and they may feel expectations of ‘doing it right’.

Understanding the nature and mechanisms of anxiety can help yoga teachers offer the tools and guiding language that recognises this state as part of the human condition. For many, simply being with themselves in a kind space can create anxiety as they meet vulnerability. It is important to be able to meet these self-protective responses and not judge them as ‘bad’, rather recognise where all of us need to foster trust in coming into feelings of safety. This can be particularly important to beginners to meditative practices – who may not have spent much time in quiet space with their inner world.

In our fast-paced and information heavy world, anxiety is on the increase as the ‘constant alert’ this continual input provokes becomes part of the landscape. Whether as deep as a diagnosis of trait anxiety (or what are now commonly termed anxiety disorders), or part of a period of chronic or extreme stress or trauma, the feelings of dread, panic, loss of control, palpitations, hyperventilation, wanting to escape and unable to concentrate are very real and very debilitating.

At times when they might be around family or friends who don’t understand these responses, they can end up feeling more isolated, unheard and unsupported. A yoga practice or class offers the opportunity to feel the kind attention, embodiment and soothing techniques that can not just help in the moment, but offer resources to bring awareness and change when a person feels stuck in anxiety.

Survival mode on constant alert

Anxiety is a part of the stress response via the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is there for self-protection and survival. It is an important part of our self-defence mechanisms to experience fear and negative thinking to save our lives in dangerous situations. However, when these heightened responses get stuck as the normal modus operandum or we react to people or situations in ways that can seem inappropriately strong, it is a sign that the ‘fight-or-flight’ stress response has become stuck in hyperarousal and continual signals that the world is ‘unsafe’.

Yoga has shown in many studies to bring down this sympathetic dominance and allow the self-soothing mechanisms of the opposing and calming parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) (Health Psychology Review, 2015; 15:1-18). Addressing this sensitivity to jump to a heightened nervous system can have a knock-on effect to other expressions of the same root cause; sleep, addictive tendencies, mood swings and the ability to act reflectively rather than impulsively under stress.

Breathing ourselves calm

In yoga, calm, long breaths as we move the body increase oxygenation, spare vital nutrients, reduce heart rate, relax muscles and reduce anxiety. This increases all-over communication throughout the body, including that between the brain, spinal cord and nerves. The brain needs three times more oxygen than the rest of the body, so increasing this supply with conscious breathing, focussing on allowing the exhale to lengthen, can have immediately positive effects on how we feel able to respond to the world around us.

Teaching tip: if you notice agitation in a student (such as darting eyes or hands), bringing the whole class to a pause for catching up with the breath and sighing out with an ‘ah’ sound can help release any pent-up tension. Making an ‘ah’ vowel shape with the mouth opens the jaw and throat, which can become restricted with stress and habitual tension held there can keep us in reactive, stressed modes.

The resilience and adaptation that yoga can help has shown to help reduce emotional interference; when we have fast reactions from the fear-based and emotional limbic system – part of our more ancient and survivalist brain. A recent study stated that “yoga may help improve self-regulatory skills and lower anxiety”, from 45 yoga practitioners and 45 matched controls, it showed that “The yoga group presented lower emotion interference……(and) rated emotional images as less unpleasant and reported lower anxiety scores relative to controls.” (Psychological Reports, 2015; 117(1):271-89)

Stilling the agitated mind – the research

From the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the second sutra (‘thread’) states that “Yoga is the mastery of the activities of the mind-field” or “…stilling the mind fluctuations”. It is this quieting or stilling the mind that draws many to yoga and has the capacity to help alleviate the racing mind tendencies that are both part of and can create anxious states. Practicing yoga with an emphasis on increasing interoception (noticing and feeling our inner landscape) helps the body awareness that switches off left-brain chatter. Being with both physical and emotional sensations as they arise through a mindful physical practice, helps those whose inner voices may tend to negative rumination and catastrophising to be with those responses without overly identifying with them.

Teaching tip: asking students to notice physical responses in terms of texture, flavour colour (non-judgemental descriptions) can help bring them into the present moment and process the experience as it is happening.

Studies have shown that the practice raises levels of the calming neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid), shown to be low in those with anxiety levels in the body (Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 2010: 1145–1152). GABA is sometimes referred to as the brain’s peacemaker, as it inhibits persistent and worrying thoughts (literally ‘stilling the mind’), allowing us to regulate brain activity, relax and sleep. Tailoring yoga sessions to focus on most GABA-inducing practices is best for those who tend to the ‘unsafe’ mode that creates constant rumination. A recent paper evaluated different needs in yoga teaching methods stated that “relaxation, breath regulation and meditation (were) very important or essential for people with anxiety”. These calming practices, can communicate to a heightened nervous system that it is safe to come down. (BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015; 15:85)

Yoga and Anxiety – Practices for Cooling, Calm and Self-care

Whilst stronger, standing poses can be beneficial to help regulate stress hormones and create resilience in life, here we are focussing on practices that are cooling, calming and literally more grounding ie close to the ground. Much of anxiety-provoking modern living has us lost up in our heads and feeling the loss of clear roots and somewhere to come back home. The ground is a supportive and trustworthy place to come back to and can help us receive the signals that there is nowhere to fall, that we don’t need to be supporting ourselves and if we can lie or sit down, we must be safe, nothing is chasing us.

Teaching tip: bringing students back to a clear sense of grounding – where they are physically in the here and now – is always a supportive place to teach from and the essence of guiding ‘embodiment’.

These practices are written as if being taught to another; you can explore how you might change instructions and guidance within your own language, retaining an emphasis of invitation and exploration, rather than enforcing ‘shoulds’ onto another person’s body.

Belly Circling

When the brain is busy and telling us all kinds of stories, focussing into what is actually true deep into our bellies can help convince our whole mind-body that everything is actually safe. Circling from the belly creates a moving meditation at both soothes and catches up the mind’s attention. From any seated position, from a lifted spine begin to circle the whole torso, making circles with the crown of your head. Keep the shoulders uninvolved and the chin drawing lightly into the throat, so that the movement comes from the belly and the front brain, jaw and eyes can stay soft.

Allow yourself to get caught up in the rhythm of the movement and it may feel organic to inhale as you lift round and back and exhale as you sweep around forward. Change direction when it feels right and fully experience the difference in flow and ease counter to the way you picked first. As with all mindful practices, when your brain (naturally) wanders, notice and bring it back kindly, but firmly – as you would a small child, without judgment or criticism. In this way, you train your mind towards more steadiness and ability to drop beneath distraction and stories of what is happening. Focus on the actual experience in your belly instead.

Viparita Karani (Waterfall practice) sequence

In this supported inversion sequence, placing legs above hips, above heart, above head allows full blood flow down from the lower body back to the heart via gravity, meaning the heart has a rest from pumping it back up. This has the effect of fully soothing the mind-body, making it a very useful practice for anxiety and insomnia.

Full-body anxiety is fed from tension in the body that can be held as part of the stress response. Taking the weight off our legs allows tension around the lower back and the tailbone to yield after staying a while with long and spacious breath. Allowing gravity to drop us in can facilitate acceptance of the feelings of release, which can be difficult for those with anxiety. This is a lovely practice to focus on emptying out, letting go, trust and acceptance.

With a bolster or folded blankets placed against a wall (with a little gap for your tailbone), bring your right hip up onto the right side of the bolster and swings your legs up the wall. Shimmy onto if you need and with tight hamstrings have the lift further from the wall.

1. Settle down into the weight of the legs and rest into breathing the shoulders to drop and the heart to rise, with your arms wherever most comfortable – closer in towards the body is more calming.

2. Wide stride inversion helps relieve stress in the pelvic floor, as this area can stay stuck over-contracted in fear-based reactions. Letting go here tells the whole body it can release.

3. Bringing the feet down to squat onto the wall helps make room for the diaphragm and deepen into the hips where we hold lots of emotional baggage.

4. Drawing the knees into the chest then raises the tailbone off your lift to create gentle length in the lower back and the safety of the foetal position.

5. Moving into a forward bend inversion (now lifting tailbone off lift) allows the back to feel supported, so we can gauge the level of leg extension the whole back body is ready for. Opening the hamstrings helps create vagal tone, our ability to self-soothe; stress often comes with tightness there.

6. Draw the legs back in to feel the ripples of opening the legs and practice smooth transitions between poses that teach us to move through life more smoothly.

7. Bring your legs back up the wall and settle the previous practice in to your body, focussing on your breath before rolling off to the side and gently coming up to lie down flat.

8. Twist in full extension to lengthen the front body. As you lift up the right knee first, drop the left shoulder heavy towards the ground to anchor the pose and open across the belly. Move to the other side. You can prop up the bent leg with your lift and stay longer if needed.

9. Always end with Savasana (corpse pose) to assimilate the practice and allow full relaxation, so that you imprint this level of self-care, self-soothing and safety.

Quick relief variation of Viparita Karani

Whenever you need to bring down a racing heart and mind, lying down on the ground can soothe your activated adrenal glands. Raising your legs above your heart allows it to begin to beat more slowly, allowing your whole body to calm down. Use a chair, sofa, bed or anything to hand and bring your hands onto your body for extra comfort.

Racing mind relief

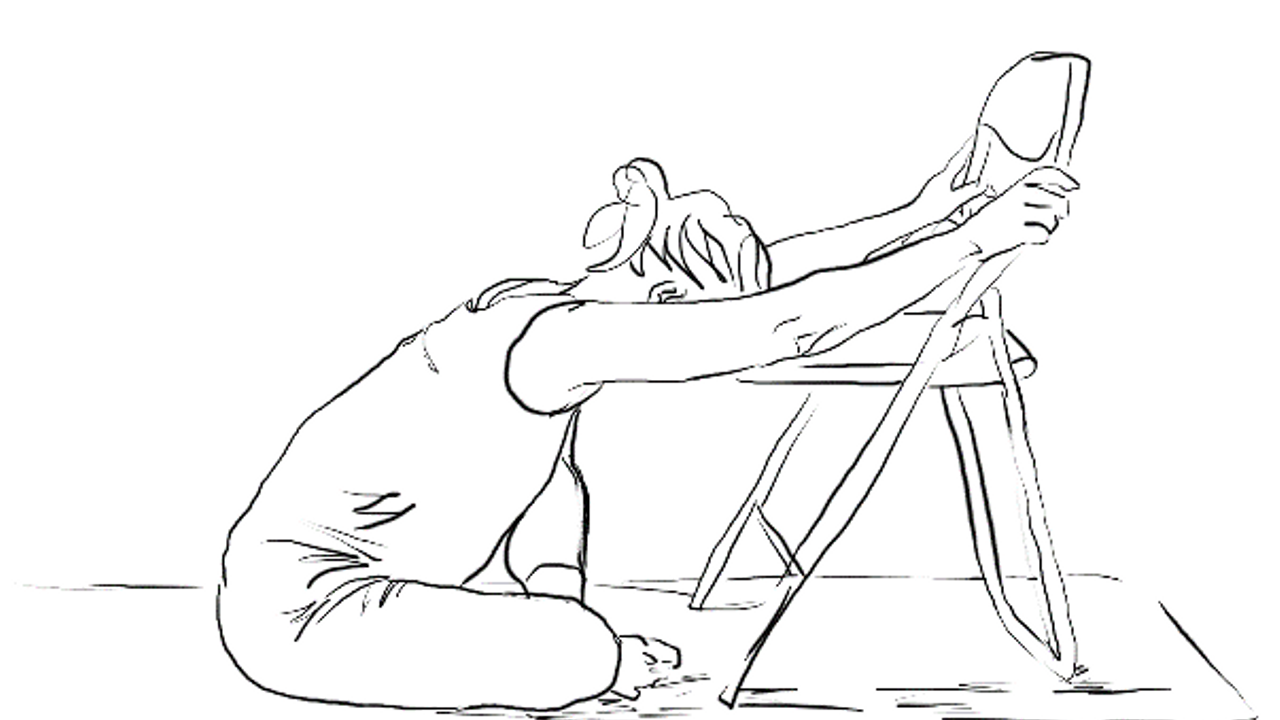

Forward bends soothe the front brain as they invite surrender when we are allowing them to unfold and not pushing in. This version to a chair can be done with crossed legs or straight out in a gentle wide stride; any position where your lower back is comfortable and you feel you can easily bend forward. Sit on a cushion or block if you feel you drop backwards and need to round the back to come forwards. Bring your forehead onto the seat of the chair (put something soft there if you need), allowing the weight of your head to create pressure their and even roll a little across this area for more soothing effects. Fold your arms onto the seat above your head to stay a while when you’re fully comfortable.

Other teaching tools for anxiety

Any meditative or mindful practice can be challenging for those with anxiety as it makes space where we can meet vulnerability. This may seem to create more anxiety at first, but finding ways to be with expanse and drop beneath negative voices is a helpful and effective skill to learn. There are many ways we can guide students to be with their inner experience that also strengthens their ability to meet their triggers with equanimity and ‘grace under pressure’.

Recognising that fear-based responses are an important part of our self-protection – rather than judging them something to be quashed as ‘bad’ – is the first call to helping them quiet. Placing a hand onto the heart or the belly offers a reassuring presence, a physical sensation to draw focus too and an area to gather awareness of the breath. We can even bring gratitude to the mind throwing up defensive strategies to protect us, but state inwardly that we are now practicing awareness instead for a more soothing strategy of safety. Simply trying to push away voices of fear can make them shout louder as they need to be heard; listening in with kindness and practicing disidentification (not attaching to the ‘stories’ the mind conjures) can give people the space they need to gauge the present moment and recognise when the narrative of the mind may be playing out something of the past, or projecting a ‘just in case’ scenario into the future. The breath in the body, in the here and now, is one of the best guides we have for non-judgmental, neutral presence.

Focussed relaxation tools can also help as offer a body focus away from mind chatter. Guiding students through practices such as Yoga Nidra, autogenic relaxation, muscle tense and release, mindfulness Body Scans and self-compassion meditations can support their ability to come into stillness after movement.

There is more information on anxiety and the relation to the nervous system in the gut (gut-brain axis), fascia, trauma and interoception (inwards sensing) in my book Yoga Therapy for Digestive Health.