Natural and Primal Movements

Jul 05, 2023

Natural and primal movements that bring you back to healthy movement patterns

To talk of natural movement patterns, we first need to accept that as modern humans, we are often (if not mostly) in postural habits that have wandered far from our original design and function.

The word ‘primal’ is bandied around much these days, but what does it mean? We can view this terminology – used to describe movement, diet and lifestyle – from two directions; firstly the word itself stems from primary, that which came first. So something primal can be the original in terms of either our evolution as a an individual within that species.

Our personal evolution

This can relate to how we evolved from fish, to reptiles, to four-legged mammals, through to primates and still have the types of motions such animals do within our whole range. We also move through these same patterns from our foetal shape within the womb to the full expression of upright human within our own lifetime (Pediatr Int.,2019 doi: 10.1111/ped.13963. [Epub ahead of print]).

Along the path of our life, various experiences, stresses, traumas, criticisms, judgements, comparisons and other conditionings come along to support or interrupt how we stand upright. How we may need to protect ourselves or feel we need to keep ourselves small can affect our whole-body expression. A common trauma (and shame) pattern held in body tissues for eg, can be a collapse in the chest and hunched posture.

In his book Emotional Anatomy (Center Press, 1985), the body psychotherapist Stanley Keleman offers; "Human uprightness is a genetic urge, yet, it requires a social and interpersonal network to be realised. Put another way, what nature intended as the development and expression of human form is influenced by personal emotional history."

When we view movement not as something we do, but rather than how we make our way through life, than we can view it more as gesture than mechanical form. This helps us break away from moving in tight, hard and limited motion ranges that can be far removed from the reaching, pulsing, spiralling, shimmying, shaking, swaying, pushing and pulling gestures of natural motion. If we sit rigidly on chairs all day and then limit our movements to similar set exercises at the gym or via fitness activities like running, cycling, then we are limiting the scope of our potential adaptability in tissues, leaving us more prone to injury. We are simply trained to do that range of motion well, often to the exclusion of others and reducing adaptability.

Even if we follow the same set routines in movement systems such as t’ai chi, yoga or Pilates we may become ‘set in our ways’; literally set into those shapes and capabilities. Changing body movement habits and including all of those animalistic forms in our evolution supports our basic functions, such as cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous system and endocrine (hormone) balance and health.

Primal movement as pleasure and play

There is little evidence on primal movement specifically. Most reported results are anecdotal and from people who have trained for years and found that shifting movement patterns from more mechanically-based and focussed on specific body parts or regions, to more fluid and primal, reduces injury, increases body awareness and relation to self. This means that rather than viewing our bodies as something separate to ‘us’, we can feel our whole being (‘body-mind’ or ’mind-body’) from the inside. This can be a difficult concept for many, as we are conditioned to separate out mind and body from a young age; to think rather than feel our way through life.

This extends into our body relationship. When we are babies and small children, we simply move and play. There is no specific purpose to this beyond moving to explore, reach for what we need, gesture what we want to express and respond to our present moment experience in ways that give us joy and a sense of freedom. Play is creative and not limited to a specific endpoint or goal; we shut down this spectrum of possibility as our movement and ‘Games’ lessons at school become about the specific rules, competing with our neighbour and getting the ‘form’ right for best performance (Children (Basel),2019;6(1). pii: E14. doi: 10.3390/children6010014).

Many follow this into the gym, running or other fitness regimes that target specific areas to fix what is perceived as ‘wrong’. Exercise forms with more play and responsiveness, such as climbing, explorative forms of yoga (eg Scaravelli), water-sports and rough terrain hiking involve the whole body and myriad shapes, responding moment-to-moment. Stepping away from counting and fixating on numbers of steps, calories, minutes and repetitions helps shift our viewpoint from what we ‘should’ be doing, to how to listen in and respond.

Of course all activities run the risk of becoming purely goal-oriented and we do derive motivation from challenge. It is not ‘bad’ per se to want to walk a certain number of miles or feel more physically able in a yoga pose, but if that takes over as the primary focus, it can quash our enjoyment and create a relationship that we must punish our bodies towards body ideals or comparison with others.

Imposing our will on our bodies to simply make them do more (often with pain and injury) can also be the relationship we expect from fitness professionals. We can be accustomed to being told what to do and doing it even if it doesn’t feel right, because surely they know better than us? But no one can feel the experience within your body for you.

When you trust your instincts (primal messages) you can move in ways that are playful and curious instead, there is no pushing in beyond your healthy (or current) range-of-motion – parts of you that have felt previously stiff, sore, painful or shut-down can begin to loosen, open up and soothe signals of distress. Playful movement is known to promote adaptability, injury-prevention, strength, balance, agility, coordination, speed, skill and mental focus and a little can go a long way.

Daryl Edwards, who developed the Primal PlayTM methodology to help people unravel from movement says; “Primal people danced, celebrated, competed, hunted, walked, dealt with nature and played. In incredibly creative and fascinating ways. You can still see of our human past in what we do today. Music, drumming, hiking, camping, fishing, swimming, gardening, sports, laughter, even dancing in dance clubs, all tap into the primal part of us.”

“We do not stop playing because we grow old, we grow old because we stop playing.”

- George Bernard Shaw

Dance and group games are often the most accessible modes of plays for adults; where embodiment, fun, joy and laughter are involved to include the release of feel-good chemicals such as beta-endorphins and other endogenous (self-produced) opioids. These increase our feelings of wellbeing and social inclusion and are known to be relieve depression, anxiety and stress-related symptoms such as inflammation and chronic pain (Front Hum Neurosci.,2017;11:410).

Exercises to unlock your primal movement patterns

The following exercises weave together most aspects of our natural motion before we stand up. Moving through the patterns we evolved with helps us to unravel any conditionings held within body tissues; often holding onto the shapes of old responses that are no longer appropriate to the current situation.

Within these exercises, feel free to play and explore as feels right for you; listening not only to your physical capabilities, but also your emotional needs. If something feels that you can do it, but it provokes a fear response (felt as tightness of breath and jaw), practice self-kindness and back out. Pushing in only reinforces the need for protection and yet more tension; but this time you are protecting yourself from yourself and your tendencies, maybe for achievement, perfection or the belief that more is better.

Curiosity and interest in where you are (rather than what you can do) allows you to settle into the pulsing, rocking, rolling, crawling and simple movement that can strengthen the most primitive movement patterns. Lightly loading areas that you mobilise is much more effective for healthy full body movement patterns than more aggressive, localised actions such as crunches or push-ups.

Linking motions through opposite aspects of the body – top/bottom, left/right, front/back, revolving in each direction, the sides and across the diagonals – creates torso coordination, where everything moves in and out brings us back to whole via the centres of the belly and heart. These are great before other forms of exercise too, especially where they include our basic motions of squatting, lunging and moving upright.

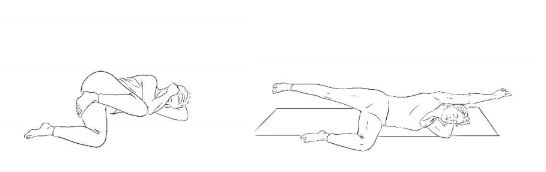

Start laying down with your feet onto the floor, knees bent. After settling into your breath, keep your feet where they are and move one knee towards your head, the other away. This knee movement won’t be massive, but it creates movement deep into the pelvic and abdominal fascia (connective tissue) to free how we move from the centre. You can feel your hips moving up and down in a side-spine undulation.

Draw your knees into your chest and move around as feels your lower back needs; you can rock, circle, roll, and open your legs to move into your hips – it doesn’t need to be anything specific or even symmetrical.

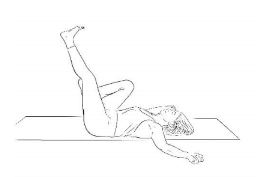

Feet back on the ground, lift one leg at a time with continual motion, as if you are walking in the air. Only straighten the leg as it feels natural to do so, taking your time to coax this out if your hamstrings feel tight.

Cycle your legs in a forward, then a backwards motion.

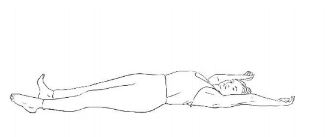

Lying out into a star position; draw one elbow down as opposite knee comes up; then both at same time.

Lying to alternatively flex and point feet; then reaching same arm as foot pointing up over head to lengthen side body.

Rock your feet on your heels side-to-side (like windscreen wipers) and then in-and-out (toes together and then away from each other) to move your thigh bones up into your hip sockets. Then rotate your feet fully to feel your ankles create movement all the way up your legs.

Roll side-to-side as you feel able, eventually resting onto one side, supporting your head with your lower arm. Inhale to bring your top elbow and knee in towards each other, then exhale to reach the top arm and leg away from each other. Repeat this as feels right, roll onto the other side and repeat there.

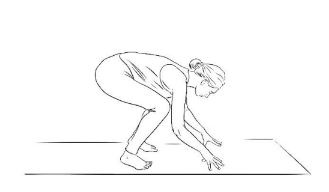

Push yourself back into a child pose with arms out to side. With your fingers onto the floor, palms gathering in and out to activate hands; from there, move in any way that explores in the shoulders, spine, neck and head.

Come back onto your belly. Draw up right leg and come onto elbows; lift left arm to bring into the same position as in child pose, so the freedom in that arm now can push up from gravity and move into any twisting, lifting or spiralling movement that feels happy through the front of the left side of the body and the lower back. Move to the other side.

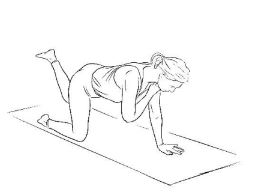

Come onto all-fours and move freely into your hips and shoulders. Then lift your right hand to the front of the left shoulder whilst you lift the left knee off the ground. Place them back and move to the other side. Move side-to-side, lifting the knee as much as feel engagement into the belly without a pull on the lower back.

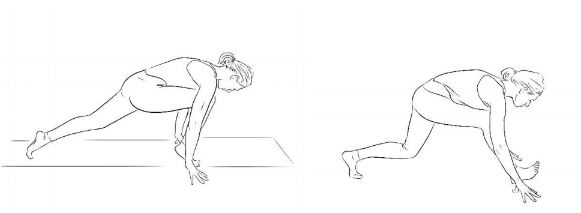

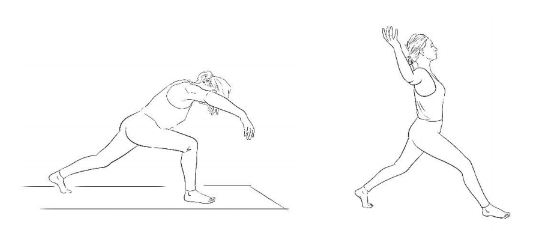

From there, step one leg forward into a lunge. With hands either side of your feet, move forward and back to ‘walk’ on the front foot and create pliability in the ankle; crucial for all freedom of movement further up the body.

Still on that side, lift into a lunge where you take the arms open and out with an inhale, forward and curled in with the exhale; moving the whole body as naturally occurs within your comfortable range. Move steps 13 and 14 to the other side.

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars, supplement discounts and more...

Bibliography

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk

- Embodied Relating by Nick Totton

- Yoga, Fascia and Anatomy by Joanne Avison

- Yoga of the Subtle Body by Tias Little

- Cranial Intelligence by Ged Sumner and Steven Haines

- Emotional Anatomy by Stanley Keleman