Exercise to reduce cravings and addictive cycles

Jan 12, 2023

We humans are wired to have neurological changes to the differing substances that can enter our bodies. Whether that is a dopamine rush from a sugar high, a glass of wine, an opioid medication, cigarette or stronger substance, these are varying degrees of changes in biochemistry that can have us coming back for more.

Whether our habitual and often compulsive behaviour patterns and use of food, drink, drugs (or behaviours like gambling, shopping, TV, excessive exercise or sex) wander into addictive territory can be subjective. When is a passion for good wine a mask for an alcohol problem or when does a cycle of pain create a dependency on pain medications for example? There is much debate whether sugar is addictive, but those caught in its thrall certainly struggle to give up and feel acute symptoms of withdrawal when they avoid it.

The definition of addiction (Miriam-Webster) states that addiction is “Compulsive, chronic, physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance, behaviour, or activity having harmful physical, psychological, or social effects and typically causing well-defined symptoms (such as anxiety, irritability, tremors, or nausea) upon withdrawal or abstinence.”

Wanting and seeking out what gives us pleasurable feelings is deep within our primal make-up. It is part of our human condition to seek and want; desire is part of our motivation dynamic. As babies we first feel this when the desire to reach a toy or procure some food provides the impetus to learn to roll over or cultivate eye-to-hand coordination. As children, quick-fix foods (usually sweet) are often wired into our neural networks as comfort or reward, so sown into the wiring and internal drives of what soothes us from an early age.

Dr Gabor Mate writes in his book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts about the role of trauma as a key contributing fact for addiction, and in When the Body Says No about how stress drives compulsions and craving. Understanding the stress and trauma connections has been part of the gathering awareness that mindful body-centred practices can help us meet and unravel the patterns we take up as coping strategies.

When the dissociation of past stress or trauma is bound up in substances or behaviours that keep us numbed, coming into feeling and presence through movement and embodiment – occupying our physical self fully in the here and now – can help us find new strategies for coping. Whether we want to move away from full-blown addiction or simply be liberated from choices we can’t seem to shake, fostering a more compassionate and present relationship with our bodies goes a long way.

Much of the research into mindful movement practices such as yoga, qi gong and t’ai chi show that they reduce the reactive, stress responses that send us towards self-medication. Much of this is due to their proven benefits in lowering stress hormones and raising soothing neurotransmitters such as GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid) that can also help post-traumatic growth (Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(5):571-9).

It is the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPCF) in the frontal brain that appears to integrate emotion-related information and translate this into habitual, quick-fix behaviours. Low VMPFC activity effects decision-making and can result in choices that satisfy instant want or reward with no long-term concern. The ‘reward’ feeling of the neurotransmitter dopamine is release not just after substances that give us a ‘hit’ or a ‘happy’, but also just from the anticipation of them. Mindful movement has shown to wake up the VMPFC response and help us make more conscious choices:

“Because yoga encourages mindfulness, positive self-talk, and self-acceptance, which may help increase self-confidence and sense of self, these aspects may engage the VMPFC by encouraging focus on body movements, the breath, and other foci.” (Explore (NY). 2012;8(2): 118–126)

How mindful physical practices can help with cravings and addictive cycles

Particularly when we slow down exercise patterns to truly feel our whole mind-body experience, we can begin to cultivate a relationship with the deeper nature of our cravings. When we can learn to stay present and breathe fully with strong physical sensations, we have more resources to meet the intensity of cravings without having to go act on them.

We can also develop more capacity for the self-compassion needed to accept the difficulties in life that can have us reaching for food or other substance or behaviours to numb the pain. A large part of these movements or positions is not simply getting through them physically, but rather breathing fully – particularly with full and releasing exhalations – whilst fully tuning inwards to the felt sense of the experience. This cultivates the ‘embodied awareness’ that helps us drop beneath the often overwhelming tide of a craving and to turn our attention to focus on the felt sensations of the breath instead. When we are also tuning in to sensations such as where our body meets the ground and how we navigate through space. Movement where we roll around and have contact with the ground has self-massaging effects. As limbs rub against each other and the floor, serotonin levels increase and help regulate our experience of pain (physical and emotional), reducing impulses to self-medicate.

This is where mindful movement helps us to drop reaction and attachment – two key facets of addictive cycles. If we can calm the nervous system and create space between a compulsion and the action of following through, or the attachment to the numbing effect that a food, drink or substance brings, we have more options available to us in terms of behaviour habits.

Focussing on the exhalation within the sensations of exercise helps us to allow release of difficult or overwhelming feelings – especially when we make noise, move the jaw and face around or sigh out. Our ever-changing breath can help us experience and accept that everything in life is ever-changing and in flux. This can help us be with those more challenging moments when we can feel hemmed in, stuck and without options. If we can tune into movement within breath and body, we can loosen around compulsive reactions, find the space for change and make it to the next moment without turning to quick-fixes we want to move away from.

“Moving meditations” where we meld movement with breath are particularly useful for taking up the mind’s focus when it may feel pulled into a craving or compulsion. Feeling alternative, embodied sensations can help us ‘disidentify’ from a craving. Disidentification involves seeing the craving as something separate to yourself and viewing it apart to create distance, noticing how you feel away from it with kind attention.

When compared to distracting strategies, the disidentification skill that can be practiced alongside awareness and acceptance, was seen to show success with chocolate cravings (Appetite. 2014 May;76:101-12). This is one of the important ways that mindfulness is becoming accepted as an effective intervention for cravings and addictions of any nature, including smoking, alcohol, drugs and sex (Sci Adv. 2019 Oct 16;5(10):eaax1569/ Curr Opin Psychol. 2019 Aug;28:198-203).

A large focus of mindfulness in any form – moving, as still meditation or being truly present in any activity – is to be fully in the here and now; without self-criticism or judgment. This is the state where we can lessen habits of labelling experience as ‘good or bad’, ‘pleasant or unpleasant’ to less polarised, critical tones. This can be challenging in a world where we are conditioned to judge, analyse, interpret, compare and categorise, but the more we can practice noticing inner experience in tones, textures, temperature or other descriptors (such as sticky, red, warm, fluid etc) the more we wire our brains into reading the present moment through non-judgmental feelings, rather than opportunities for harsh inner voices.

Exploring this within an introspective movement practice such as yoga, qi gong or t’ai chi can help to soothe hypervigilant inner voices; bringing more relaxed inner attention to thoughts and feelings that may trigger temporarily rewarding impulses. Identifying these patterns can help us attend to the deeper needs that cravings and addictions are crying out to fill; often rooted in kindness, care and connection with others.

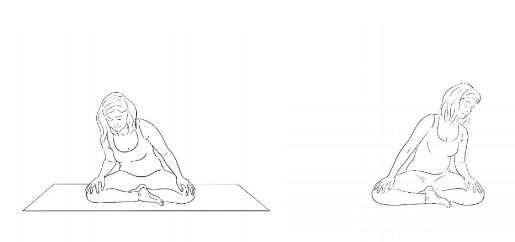

Belly Circling

From any seated position, from a lifted spine begin to circle the whole torso, making circles with the crown of your head. Keep the shoulders, jaw and eyes, so that the movement comes from the belly. Inhale as you lift round and back and exhale as you sweep around forward. Change direction when it feels right and fully experience the difference in direction in this moving meditation.

Lower back and hip release

We hold much emotional tension held in our belly, lower back and hips; it is helpful to explore these areas lying down where you are fully supported by the ground. Lying with legs bent, take one leg up at a time to explore any movement that simply feels good - tuning into your body’s needs; listening and responding.

Shoulder, upper back and neck release

From kneeling, take your hands out wider than your shoulders, elbows above wrists with your palms drawn up so just your fingertips are on the ground – you can place your hands higher onto a chair seat if needed. From there, explore any motion into your shoulders, neck, spine, back, hips, face and jaw; getting into the nooks and crannies were tension can be held and translate into craving.

All-fours moving meditation

Starting on all-fours, move around naturally, exploring whatever feels freeing in hips, lower back and shoulders. Then exhale down towards a child pose and inhale back up to all-fours.

With the same breath rhythm, then take the hips out to one side as you exhale down and up the other side as you inhale. Follow these pelvic circles and then switch to the other side, resting in child pose after.

Then inhale up to lift the right arm forward, left leg back, drawing the lower ribs in to support the lower back. Exhale back down to child pose, then inhale up with the opposite arm and leg; moving side-to-side.

Side-body length

From all-fours, step one leg out at a time behind you and across the body to lengthen the whole side, including the neck as you look around to see the foot. Also feel the side movement into the spine as you move side-to-side; releasing tension there we don’t often get into with modern movement patterns.

Opening the front body

Coming onto your belly, lift up onto your elbows to feel length in the front body and opening across the chest; breath there a while with chin dropped towards the throat. Then bend up one knee to bring the inside of that leg onto the ground comfortably for the hip and take the opposite arm out to the side as you did before. Explore similar motions through the shoulder, neck etc, including turning to look over each shoulder, feeling your range of motion according to how your lower back feels. Do each side and then rest fully onto your belly for a few minutes to feel your breath there.

Soothing the forehead

Supporting the head to a chair during a forward bend, we can let go of its weight and soften the eyes, jaw and mind. With arms folded onto the seat – legs crossed or sitting onto a block as needed – rolling the head to massage the forehead can encourage soothing the nervous system (parasympathetic and vagus nerve) via the trigeminal nerve there.

Soothing relief

To end a practice or whenever you need to bring down the racing heart and mind that can accompany the agitation of a craving, lying down on the ground can soothe your activated adrenal glands. Raising your legs above your heart allows it to begin to beat more slowly, allowing your whole body to calm down. Use a chair, sofa, bed or anything to hand, support your head as needed and bring your hands onto your body for reassurance and tuning into the breath there.

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars, supplement discounts and more...